Mother Steals a Bicycle and Other Stories is a children’s book by Salai Selvam and Shruti Buddhavarapu. The illustrations are by Tejubehan.

__________________________________________________________

Mother – daughter stories are like a game of dots and boxes. You take turns to draw lines on the dots and only one of you wins. But the boxes, like stories – are complete because the two of you sit together and draw them.

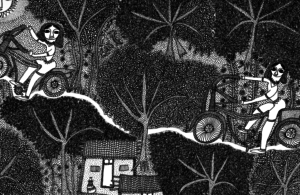

When ‘Mother steals a bicycle and other stories’ begins, the 11-year-old daughter already knows what stories to ask from her mother and the mother is just as eager to tell them.

“Amma’s best stories are ones where trouble actually comes looking for her” says the daughter suggesting that in the other stories, it’s usually her mother who goes looking for trouble. Even so, the girl has decided that the bicycle story is the best.

And so the mother tells us about the time she stole an uncle’s bicycle and took off with it. Of course she didn’t know how to ride it – she just learnt it on the way — as she rode it screaming through the village.

My favourite part of this story is when she realises that she may have learnt how to ride it but she has no idea how to stop it. So on and on she goes into two, three villages.

When the girl asks, “But why didn’t you stop amma?” – I believe nobody is prepared for the answer.

Amma says – “Back then I really thought that the cycle was only meant for paths, and that if there were no paths, the cycle would automatically stop working”

Image Credits: Tara Books

***

My mother has never told me stories. What I gathered were stolen from her when she wasn’t looking. She’d only tell me bits from her childhood that were meant as lessons: “Stop fighting with your sister. Learn to share. I had to share everything with my two brothers and three sisters when I was young.” “You should call yourself lucky. We never had money to buy napkins. When I got my period, I used cloth”

She only gave me dots and I drew the lines– Maybe the cloth was beige in color with faded orangish spots. Maybe she hid her new frock under a cot one day – hoping her sisters wouldn’t find it. Maybe she never learnt to ride the bicycle, maybe she climbed big trees when she wanted to hide from her mother.

***

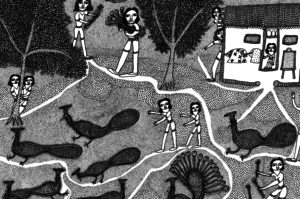

All the eight stories in the book happen outside home. Even if they begin at home, the mother pulls them out by the ear and makes them happen outside. Like the eighth story in the book where at midnight, the mother sneaks outside with leftover food to watch ‘all the interesting people who worked in the dark’ (rabbit hunters, night fishermen, water supervisors.)

In the second story, she and her gang of friends take the forest route towards school – the longer, the more adventurous one – filled with monkeys, snakes, and peanuts (but amma didn’t you have to get to school on time? Oh we didn’t care – we remembered school when we saw it and then we ran towards it)

Image Credits: Tara Books

In the fifth story she tries to catch a peacock because she wanted to sit on it. In the seventh she volunteers to act in village plays where she says she loved wearing turbans and fake mustaches to play men.

In the third, she teaches herself how to swim (Sometimes we set ourselves complicated goals. We’d tie an egg into a towel that we wrapped around our heads. The goal was to swim from one shore to the next without breaking the egg)

Whether it is befriending her own shadow and playing with it or going in search of cicadas to put them in a matchbox and listen to their humming sounds – the worry that someone could be waiting at home never overpowers her fascination with the outside world – and that is a delight to listen to – especially when women tell us these stories.

Image Credits: Tara Books

***

When my grandmother told me stories from her childhood, she began every story by telling me she woke earlier than anyone else in the house to go collect firewood. After this point, she’d usually lose interest in telling me the rest of the story. And the other parts of her day and her childhood were left to my imagination.

One day she told me she loved eating jack fruit seeds so she’d put them out to dry in the backyard where the sun fell. She’d sit by the door and watch them. Today when I think about her, I see a young girl sitting by the door, hands knotted together, legs spread far, her eyes soft, now closing now waking, but always – watching the jack fruit seeds.

***

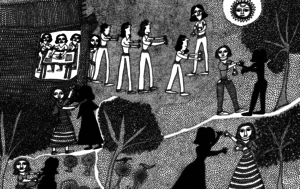

I am curious about what our mothers’ and our grandmothers’ bodies must have been like when they were young. How they looked when they bent and walked. How they lifted firewood and pots and hoisted them up. How they jumped and how they sat.

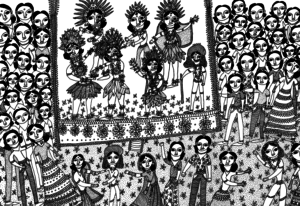

And that’s why the illustrations of the young girls and the women in the book are special. Much like the stories, the bodies of the women in these illustrations are agile and full of life. It is oddly liberating that neither the older girls nor the women carry the weight of breasts. It’s almost as if their bodies are shadows.

Image Credits: Tara Books

The words are agile too. Like the illustrations, they too seem unburdened and shadow-like.

Some words in the book are chosen to act out their sounds and meanings. So the word ‘bolt’ really ____bolts___ and the word ‘float’ floats.

***

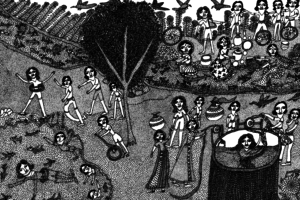

In the sixth story we see that the mother’s favourite thing to do as a kid was to play with her own shadow.

“Oh, I never tired of playing with my shadow – I loved her. The second I stepped out into the sun or under lamplight, she’d appear. She was always there for me. I’d say, let’s run, and she’d run. Stop! And she’d stop. I loved her because she did everything I asked her to.”

Somewhere in the business of living in a city with tall buildings and never having to walk anywhere, I think we have forgotten our shadows. Are they still alive? Do they still follow us? Do they not like cities?

In the games that our shadows play with us and the stories that our mothers show and hide from us – this book weaves a finished game of dots and boxes.

Even so, unlike boxes – stories have a way of belonging to no one – not to the one who tells it, not even to the one who listens to it.

Then whom do stories belong to?

Image Credits: Tara Books

***

You can buy the book here.

Latest posts by Vijeta Kumar (see all)

- A review of Mother steals a bicycle and other stories - 17th November 2018

- What happened when Bengaluru’s working class women had a #MeToo meeting? - 7th November 2018

- In which I learn how to deal with peeps too cool for Kannada - 20th February 2018

Aicha HOCINE 16th August 2019

Thank you very much for these stories. As a reader, I have been emotionally involved in the way the writer is playing with words to illustrate the wisdom behind the mothers’ stories. The significance of these narratives lies in the fact they are told to enjoy, teach and COMMUNICATE. Reciprocating what others say and translating their speech to behaviour is itself a pedagogical method of the teaching-learning process that the new generation may require. Teaching children to listen to others can build their future and reshape their personality.

The Open Dosa Team 29th August 2019

Thank you so much for reading and taking the time to respond, Aicha! 🙂

Hope you are well.

-Vj